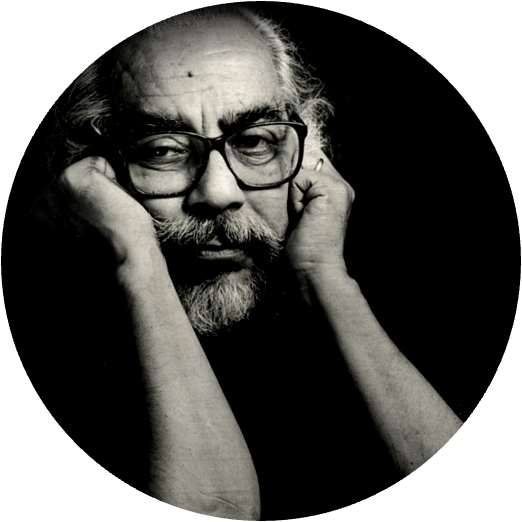

Krishen Jit loved the theatre very much.

And, mostly it loved him back.

It gave him many friends and collaborators, an unending flow of work till the end of his life at the age of 65 in 2005, a reputation for experimental work in the Malay and English theatres, and, the place of an intellectual who advocated for the arts as a shared public space for art-makers and their audience to explore and re imagine their divided selves and nation.

Krishen was a theatre artist who studied history. This must surely have been very useful to someone like him living in a society with a long past that underwent radical changes over a very short time – from colonial rule – to independence – to racial ruptures – to the state’s attempts to build a new nation through social engineering – to the rise of Islamic conservatism.

It may surprise some people to discover that he had had no formal training in theatre. He learned to do theatre by doing theatre since his teens, and from studying traditional and contemporary practitioners in Malaysia and elsewhere, alongside performance theory and history. He kept his mind and practice open with continual research, experimentations and reading/watching all sorts of things – from academic books to lifestyle magazines, Bollywood movies, Malay and English newspapers, and watching street life from Chinese coffee shops.

In his personal life, and also through his theatre, he dealt with prevailing issues of race and racism, by simply refusing to obey identity boundaries. For example, his ‘colour-blind’ casting, which led to complex multicultural performances, was indifferent to the actors’ race and gender, class, etc. He had used a Chinese and a Malay actor to play two Indian characters on a rubber estate [K.S. Maniam’s The Cord], a solo woman actor to play three men (Chinese, Indian, Malay) who were trying to build an atomic bomb for the government [Huzir Sulaiman’s Atomic Jaya], and an ensemble of multi-ethnic, multilingual, multi-national actors to perform four generations of a rags-to-riches Chinese clan [Leow Puay Tin’s Family].

So, although he didn’t set out to make political theatre, there was often a political dimension to his work, when, through his actors, real-world politics would seep in.

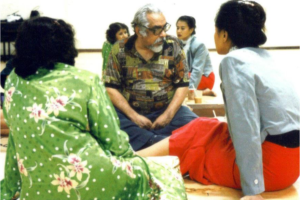

Sometimes he would challenge his audience by putting in things that didn’t seem to ‘belong’, such as having his actors do tai chi whilst speaking their lines, or, using a tikam-tikam to pick scenes to perform during a performance. He loved and respected his audience – check out his director’s notes to them – and trusted them to figure things out for themselves. In return, they could always expect him to deliver a good show – because he would have worked his actors very hard, to find the human truth of their characters in themselves.

Here’s the background story. Krishen was born in British Malaya, in 1939, to a Punjabi cloth-trading family. One of three sons, he lost his father early on and grew up in an extended family, in Batu Road and Jalan Travers in Kuala Lumpur.

As a kid, he was hooked on watching whatever movies and street theatres were available then. He received a colonial schooling in English which introduced him to literature, history, debating – and acting.

He studied for a history degree at the University of Malaya [UM] – where he began to direct – before going for post-graduate studies in American history at UC Berkeley.

He had returned to teach history at UM, when racial riots broke out in May 1969 – he would later say it showed him how little he knew of the country.

Wasting no time, he was 30 then, he learned and mastered the Malay language. And along with his Malay peers, he left the still-colonial English-language theatre to help develop a new modern theatre for Malaysia, in the national language.

He directed and produced for the Malay theatre, while supporting writers, visual artists and other practitioners who wanted to create new, distinctive, Malaysian works of art. He wrote untiringly about the theatre and related arts in his weekly newspaper column for the benefit of a general audience.

Krishen broke off with the Malay theatre, after anonymous letters were published in the Malay press against him as the artistic director of a Malay theatre festival, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Malay Studies Department at his university, in 1979.

He continued his advocacy for original Malaysian theatre and art-making by co-founding an artist collective, Five Arts Centre, with Marion D’Cruz (dance), Chin San Sooi (theatre), K.S. Maniam (writing) and Redza Piyadasa (visual art).

If he felt hurt by the 1979 rejection, it didn’t stop him from helping to launch the National Arts Academy under the Culture Ministry in 1994. He headed the theatre department where the predominantly Malay students were exposed to traditional Malay and contemporary performance practices, from being taught by practitioners from diverse theatre and ethnic backgrounds. Given time, under his watch, this could have become the seeding of a new strain of Malaysian theatre. But four or five years later, he resigned in protest against the management’s decision to restrict what students could perform in their projects.

Being jobless was actually the best thing for him then. It allowed him to do the thing he loved the most – directing. And he maxed it out, in what would turn out to be the final turn in his career. While continuing to do experimental work in Kuala Lumpur, he also directed for the professional, commercial theatre in Singapore, using a mixture of new Singaporean and well-known Broadway-West End plays.

Krishen was married twice, first to Margaret Yong, an English Literature academic. He had a son from the marriage. In 1986, he married Marion D’Cruz, his partner in life and in art, who produced many of his projects. She continues to be involved in the Five Arts Centre and is the manager of the Krishen Jit Fund, which was established in 2006, to honour his memory and work.

By Leow Puay Tin

31 March 2023, KL

All photos © Five Arts Centre